Most strategy problems are actually foresight problems.

Not because we can’t analyse—but because we keep mixing now, next, and later. That timeline blur is why decisions loop, agendas overflow, and “alignment” stays fragile. That is why the Three Horizons framework has become one of the most practical foresight tools for leaders and boards because it restores temporal clarity—the starting point of good governance.

What is the Three Horizons framework?

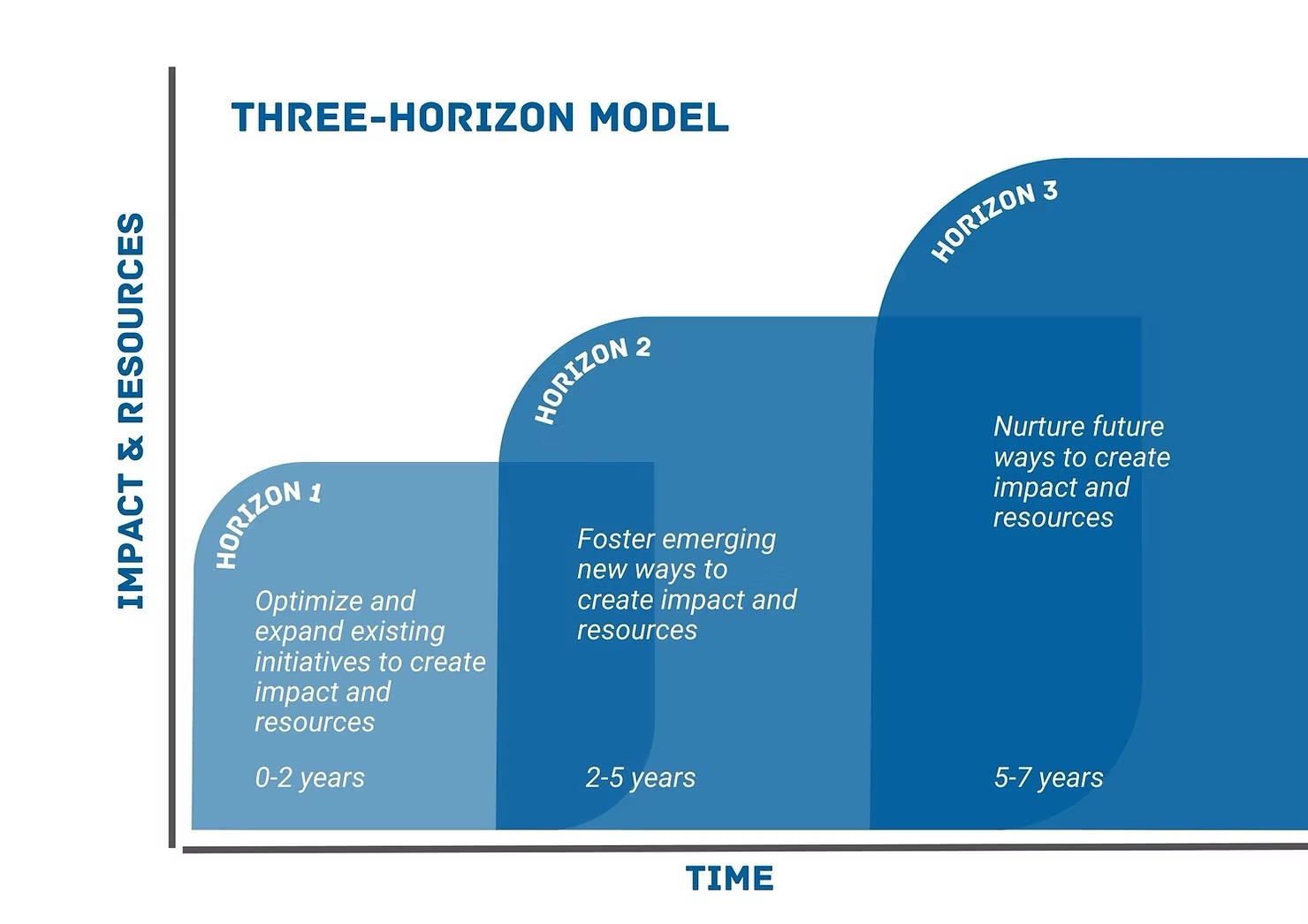

The Three Horizons framework is a simple way to separate three kinds of work that coexist inside any organisation:

- Horizon 1: the current system that must keep working

- Horizon 2: the transition period where experimentation and trade-offs intensify

- Horizon 3: the emerging future that requires preparation and capability-building

It is not forecasting. It does not predict what will happen.

Instead, it helps leaders and boards use the right decision criteria for the right timeframe.

This is exactly what many organisations struggle with today: applying Horizon 1 metrics to Horizon 3 choices, or expecting Horizon 2 transitions to behave like stable operations.

Where does it come from?

The Three Horizons concept has two major lineages—both relevant for AIRIS readers who care about strategy, governance, and decision-making under uncertainty.

1) Corporate strategy: the “three horizons of growth”

In business strategy, the “three horizons” framing became widely known through McKinsey-associated work on growth and portfolio thinking—often referenced through The Alchemy of Growth (Baghai, Coley & White, 1999) and later McKinsey “enduring ideas” on the topic.

This strategy lineage focuses on balancing:

- core performance (today’s business),

- emerging opportunities (next),

- and long-term growth bets (future).

2) Foresight and transformation practice: the “Three Horizons” of systems change

In the futures and systems-change community, the model was developed as a practical framework for navigating transformation—particularly through the International Futures Forum (IFF) and practitioners such as Bill Sharpe, along with collaborators including Anthony Hodgson and Graham Leicester.

Bill Sharpe’s book Three Horizons: The Patterning of Hope (2013) helped popularise this practice-oriented version, and later academic work framed it as a “pathways practice” for transformation (e.g., Sharpe et al., 2016).

For AIRIS, this second lineage is especially relevant because it treats Three Horizons not merely as strategy categorisation—but as a way to govern change in complex environments.

Why leaders and boards use it

The Three Horizons framework helps with a core governance challenge: organisations must do three things at once:

1) Protect the present (without becoming captive to it)

Boards and executives must sustain reliability: operations, compliance, safety, continuity, trust. Horizon 1 is legitimate, and often non-negotiable.

But when Horizon 1 dominates the agenda, the future gets postponed indefinitely.

2) Navigate the transition (where uncertainty is unavoidable)

Horizon 2 is where many strategies fail: not because the future is wrong, but because the transition is messy.

This horizon requires:

- experimentation,

- trade-offs,

- capability-building,

- and governance guardrails.

It’s a different leadership mode: less “optimise”, more “learn and adapt safely.”

3) Prepare for future viability (before it becomes urgent)

Horizon 3 concerns long-term relevance and legitimacy: new technologies, stakeholder expectations, regulatory shifts, energy transition dynamics, or entirely new operating models.

Boards rarely regret investing too early in understanding Horizon 3.

They often regret realising too late that it had arrived.

Where it applies (real-world use cases)

This framework becomes particularly useful in:

- Board strategy discussions when operational urgency crowds out long-term stewardship

- Transformation programs where “change fatigue” grows because timelines are blurred

- Innovation governance (how to evaluate pilots vs. core performance)

- AI governance (risk and compliance today vs capability and value tomorrow)

- Energy transition strategy (reliability now, transition constraints, future system design)

In short: the Three Horizons framework is a tool for long-term decision making that remains grounded in present constraints

Related AIRIS reads

If this resonates, you may also enjoy:

- How to Cascade Strategic Foresight Across the Organization: From Boardroom Vision to Frontline Action

- How to Build a Culture of Innovation in Decision-Making

- AIRIS Blog (for more on anticipation, resilience, and decision-making)

Other resources

Three Horizons Framework – a quick introduction

The Three Horizons framework explained by Bill Sharpe